2018-07-05

A multi-disciplinary team led by Dr. Chris Overall are a step closer to turning off the lights on inflammation—in oral health think periodontal disease—as well as understanding more about the mechanisms behind autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis.

In a significant paper† published recently in Nature Communications, investigators from UBC and several institutions†† discovered how to switch macrophages from the kind that can cause damage to the type that restores tissue.

Macrophages are white blood cells that control processes like wound healing, infection and tissue damage. These processes have two phases—an inflammatory phase where the damage or infection is tackled, and a healing phase where the tissue is repaired. These phases are controlled by two different kinds of macrophage—the pro-inflammatory macrophage is switched on by a signaling protein, or cytokine, called interferon-gamma (IFNγ), whereas the healing kind of macrophage is turned on by the cytokine interleukin-4 (IL-4). If the pro-inflammatory macrophages are not turned off so not replaced by the healing kind, chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases like arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can develop.

More than 15 years ago, the Overall Lab discovered that other cell signaling proteins can be switched on or off by cutting at the start or end of the protein chain. This is carried out by cutting enzymes called proteases, in particular by proteases called MMPs. Macrophages make a protease called MMP12. The Overall Lab showed that mice without any MMP12 have worse arthritis and SLE disease, suggesting that MMP12 is important for the healing phase that follows inflammation.

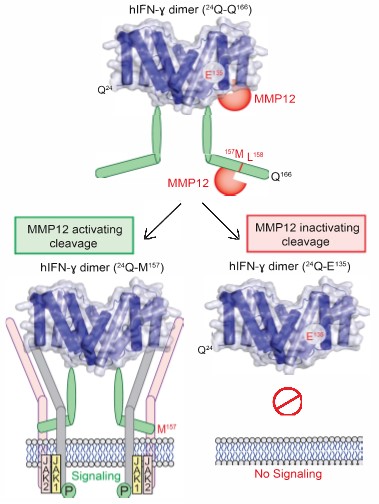

Now the team has discovered a new cytokine target for MMP12. Dr Tony Dufour in the Overall Lab showed that normally at the start of healing MMP12 makes two cuts at the end of the IFNγ cytokine. The cut IFNγ can no longer stick to receptors on the cell surface. Without this “on” switch, the pro-inflammatory macrophages are no longer active, which allows the healing IL-4 activated macrophages to take over. In the absence of MMP12, or if MMP12 is blocked by a drug, IFNγ signaling is prolonged, pro-inflammatory macrophages accumulate, and in mice, arthritis and SLE disease is worse. The group then realized that the protease MMP12 is decreased in SLE patients compared with healthy people. Thus it appears that removal of the end of IFNγ by MMP12 is important to turn off pro-inflammatory macrophages and to allow tissues to return to normal. Without this off switch, chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases like periodontitis, arthritis and SLE can occur.

“The next step is to develop drugs to increase protective levels of MMP12 in patients with non-healing SLE and chronic inflammation,” says Chris Overall. “In the meantime, we can use low levels of MMP12 as a new biomarker to indicate patients that are at risk of ongoing disease, who may benefit from stronger anti-inflammatory treatments.”

†Dufour A, Bellac CL, Eckhard U, Solis N, Klein T, Kappelhoff R, Fortelny N, Jobin P, Rozmus J, Mark J, Pavlidis P, Dive V, Barbour SJ, Overall CM. (2018). C-terminal truncation of IFN-γ dampens proinflammatory macrophage responses and is deficient in autoimmune disease. Nature Communications. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04717-4.

††Commissariat a l’Energie Atomique CEA-Saclay, Labex LERMIT, Service d’Ingénierie Moléculaire des Protéines (France); Swissmedic, Swiss Agency for Therapeutics Products (Switzerland); Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, McCaig Institute for Bone and Joint Health, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, and the departments of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Medicine, Oral Biological and Medical Sciences, Pediatrics, Psychiatry, Centre for Blood Research, Centre for High-Throughput Biology, Child and Family Research Institute and BC Children’s Hospital, University of British Columbia (Canada).